Why I love Hyman Bloom’s Paintings

Hyman Bloom’s New York Times obituary opens with a fantastically backhanded compliment.

A mystical and reclusive painter who for a brief time in the 1940s and ’50s was regarded as a precursor to the Abstract Expressionists and one of the most significant American artists of the post-World War II era, died on Wednesday in Nashua, N.H.

How did Bloom turn from art-world darling to apostate? And did he really deserve such a snarky obituary?

If you’ve seen any of Bloom’s goriest paintings, you might be unsurprised, even relieved, to find his art buried in obscurity. “A Matter of Life and Death,” a recent exhibition of Bloom’s paintings at the Boston MFA, was filled with depictions of decaying corpses and bloody autopsies. The works might have reminded you, like one of my fellow visitors, of the gratuitous violence of the TV series Dexter. Turning your face away from the canvases, you too might have explained: “I don’t want to know a mind like that!”

I’d like to show you some paintings which might lead you to reconsider, maybe even catch a glimpse of beauty behind the blood.

In this exhibition full of cadavers, the painting which upsets me most shows a living woman. She’s old, very old, and completely naked, her body a heavy sagging. You can feel its weight, its emptying. It — she — is sitting in an equally bare landscape — a world sliced in half by a lumpy, menacingly near horizon.

Her body is an hourglass, bottom-heavy. You can almost see the sifting. The tips of her fingers are already dissolving into grains of sand.

She’s sitting below a blank sky, on the edge of a dark, earthy precipice. On the edge of her own grave. Soon, she will simply vanish downwards in a puff of dirt. For now, she looks away, her toothless mouth widening in a grimace.

This looking away is what upsets me most. The body goes where it must. It is obedient. The mind, chained to this inevitability, winces. It turns away — though there is no turning away.

There is no turning away: if you follow the woman’s gaze out into the next room, you’ll find that it leads straight to her inevitable future — to Female Corpse, Back View.

The body is lying face-down, irrevocably pressed against this flat brown surface, this dead end. There is nothing but the hard cold earth.

And yet… we are viewing this from above — so there is an above, a hope.

Our bodies are parallel to this body. So it is standing up, in a gate of shroud, of bone, of paint. No one can stand on feet like these, but the body is a fish, swimming upwards.

We are viewing this from behind — standing in line to the gate to nowhere.

Why were these rich paintings forgotten?

Antisemitism may have played a role. The critic Hilton Kramer compared Bloom’s paintings of rabbis, cantors, and the interiors of synagogues to “gefilte fish at a fashionable cocktail party.” Kramer didn’t exactly undo the damage by later explaining that his remark was just “one Jew against another.”

But that can’t have been the whole story. After all, we still remember Marc Chagall. A more surprising (considering the painter’s identity) prejudice played a role in the poor reception of one of Bloom’s paintings.

Female Corpse, Front View and Corpse of an Elderly Male are bloated, repellent jewels. The bodies decay into a shimmering mess of paint. It’s hard to look, impossible to look away.

These two paintings were shocking in their day — but not equally shocking. Reasoning that “the Woman is a much finer picture than the Man,”1 Bloom’s gallery owner tucked away the latter — but not the former — in a back room, viewable only by special request.

Why were the paintings treated so differently? As far as I can tell: sexism with a dash of homophobia. Strike one: the corpse was male. The viewer, who was presumed to be a man, could distance himself from the female corpse, see it as a mere object — but viewing the male cadaver meant staring his mortality in the face. Strike two: the corpse was nude. Male nudes have been censored throughout art history. After all, if the only sexual desires which count are those of straight men, why would you even want to paint a nude man?2

Today, the only difference between the male and female nudes is that one has a penis. Which of our aesthetic judgments will our descendants find equally laughable?

Maybe you think both corpses should be tucked away in a back room. Fine. But why were Bloom’s other, gentler works forgotten?

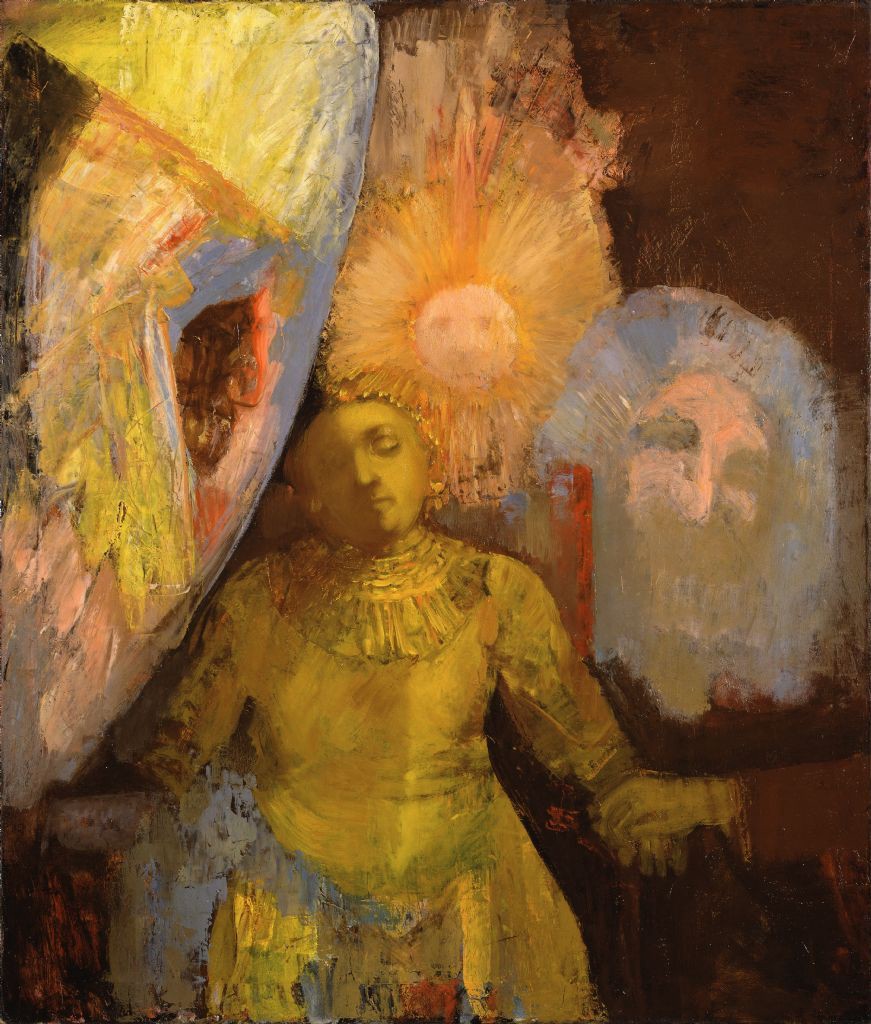

Take Christmas Tree. Everything I love about Bloom’s oeuvre is present in this early painting. Made of light and hope, it feels sacred. The tawdry ornaments turn me into a toddler on Christmas Day.

In crucial places, where the painting ought to be convex, it almost seems concave — like a gaping hole at the heart of a mystery. In fact, the tree is a gaping hole: the painting is more red than green, a tower of ornaments piled over a smattering of branches.

This is one of Bloom’s signature paradoxes. His paintings lie at the meeting-place of flatness and depth, interior and exterior. They urge us to go beyond the surface, to excavate and to dissect — and yet they themselves are only surfaces.

There’s one more thing I love about this work: the paint in Christmas Tree forms an unbroken swirl. I imagine removing a single brushstroke, and it’s like pulling a plug in a bathtub; everything would drain away.

You could call this unity “beautifully balanced design” or perhaps an abstract “allover.” But when I look at Bloom’s paintings, I experience the impossible unity of his works not as an aesthetic ideal, but as a spiritual truth. The works are one because the world is one — and I am one with it.

Whether they represent Christmas trees or cadavers, all of Bloom’s paintings take me to that same place of wholeness.

That may be because they all come from the same place: they all have their roots in a single transformative experience. One night in the fall of 1939 (soon before painting Christmas Tree), Bloom, alone in his studio, “felt himself transformed into a boundless being, caught up in an ecstasy of color.” He “had a conviction of immortality, of being part of something permanent and ever changing, of metamorphosis as the nature of being. Everything was intensely beautiful.”

He would be painting that experience for the next 70 years of his life.

Well, that plus its exact opposite:a time of irreparable horror. Earlier that fall, Bloom had had to identify the body of his close friend Elizabeth Chase in the morgue. She had committed suicide.

Death and wholeness. Wholeness and death. From now on, he would grasp these twin experiences, pieces of the human puzzle — one in each hand — every time he began a painting.

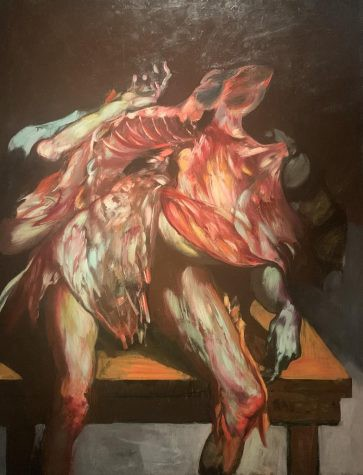

In The Harpies, eerie monsters are tearing apart a body. Elaine de Kooning singled out the painting for praise, approvingly quipping that “composition, progressing toward total abstraction, seems to devour the subject.”

But while individual works such as The Harpies leaned toward abstraction, Bloom’s oeuvre as a whole was headed in a completely different direction. Just as the art world embraced Abstract Expressionism as the only “progressive” style, he moved further from the mannerism he had helped to create. As he explained,

the Abstract Expressionists, Jackson Pollock, for example, hurled themselves at the paintings with a destructiveness that was a form of nihilism, destroying everything because the world was not to their liking. (…) What I was trying to create was a complex picture in the classical sense; a work with depth and subject matter that was readable and over which I had exerted control. I thought of art as elevating, and I didn’t think Jackson Pollock even had a foot on the ladder.

Bloom painted bodies sliced open; Pollock splashed paint onto canvas. And then Bloom had the gumption to call Pollock’s work “destructive!”

He was right.

The Harpies represent (among other things) the cycle of life and death, the beauty and terror of the bacteria which will devour our bodies after our demise. The painting hovers on the edge of chaos, yes — but only because the world does. It may be “progressing toward total abstraction,” but it will never get there. To get there would be to give up the animating tension, the redemptive kernel which is the whole point of Bloom’s work.

The way I see it, Bloom’s paintings are mandalas. They are maps to the universe and keys to spiritual experiences akin to the ones which started Bloom’s career. (One of the paintings, Treasure Map, is a literal map.) They weave together shattered objects into dense, unbroken tapestries.

Each painting is a step on a quixotic quest: capturing the universe in a single canvas.

Disappointed at the reception of his cadaver paintings, Bloom exclaimed “I thought they would thank me!” Hardly the words of someone wanting to shock… (He had no intention of shocking when he continued: “the human body is beautiful, inside and out,” either — though admittedly those are just the words a murderer like Dexter would have used.)

What are we supposed to thank Bloom for? What did he think he was giving us?

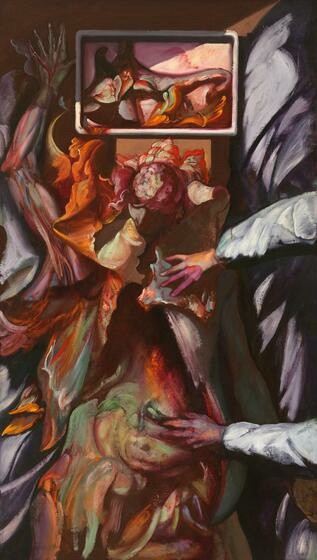

I see an answer in The Anatomist — a self-portrait of sorts. Like the anatomist, Bloom opens up the body again and again, not gratuitously, but to learn something. Like doubting Thomas, he places his finger in the wound so that he might believe. In what? At times: in the resurrection. At other times: in his own mortality.

I remember what I felt in front of Seated Old Woman: nothing is more heartbreaking than turning away from death until it’s too late. Bloom didn’t want to end up like her.

I think this is why he oriented The Anatomist vertically. If he had rotated the painting by 90 degrees, he would have shown the anatomist’s — his own — perspective. Instead, he gives us three hands (two living, one dead) made of the same stuff, species of the same genus. He gives us a mirror.

Or maybe we’re hovering above, beyond, the body. Either way, the painting occupies an eternal, multi-temporal viewpoint which includes life as well as death.

Its orientation is towards final matters.

You can neatly slice the Cadaver on a Table into an upper and a lower half. One half is sinking; the other soars skywards. One hand points to the ground; the other opens to the heavens. In a perfectly balanced tension — or a perfectly tense balance — the two gestures almost send the whole thing spinning.

The cadaver is rudely thrown onto a wooden table. This turns the body into a slab of meat, a mere thing. At the same time, the table’s edges form a triangle, offering the flesh-flaming body up to the heavens. At the apex of the triangle — the cavity in the cadaver’s chest.

That gaping hole — that tunnel — is the spiritual center of the painting — and of all these paintings of dissection. Their subject is precisely what isn’t there: the departed.

Bloom, who believed in an afterlife, studied astrology, theosophy, and occultism. He searched for spiritual truth in unusual places, taking LSD as part of a psychological study on creativity and attending (and painting) seances. These facts make it easy to dismiss the spiritual themes in his work — and, honestly, make me feel embarrassed to defend them. But when I look at his paintings of the deceased, I viscerally feel the beauty of his faith. It’s a faith I don’t share, but I’m grateful to be able to try it on through these works. They help me look more kindly on people I’d otherwise label “foolish.”

Even without the promise of an afterlife, I find hope in nearly all of Bloom’s paintings — hope in the very emptiness of the bodies. At times, it lies simply in honoring the departed, in the contrast of what was there a moment ago with what is not. Other times, it’s just the opposite: the works uncover an emptiness, something that had been missing long before death. Concavity instead of convexity. As if the thing I’m most terrified of losing was never there to begin with.

Somehow, that makes it okay.

If Bloom’s paintings had merely been shocking, he wouldn’t have been forgotten. Just think of the work of his contemporary Francis Bacon (who once had a joint exhibition with Bloom), whose paintings were made of blood and hopelessness. Or think of Duchamp’s urinal. In the art world, shock value is a feature, not a bug.

Bloom’s work benefited from this for a while. In fact, Severed Leg, one of his least redemptive paintings, hung the dining room of MoMA curator Monroe Wheeler. Imagine sipping cocktails below it!

Painted against the hopelessness of a blank wall, the Severed Leg is achingly disconnected from the rest of the world. Bloom’s other dissection paintings aren’t like this. In front of these paintings, which ought to have shocked me most, I lose even the qualified, mesmerized sort of repulsion I experienced in front of the male and female corpses.

It’s hard to explain my immunity to these works’ ostensible violence. They’re so much gentler in person than in reproduction — as if their aura could take me in its arms and shield me from their horror.

In photographs, these are unambiguously paintings of flesh; the red is undoubtedly blood. In person, the flesh is fully flesh, but also the most mesmerizing, caressing paint. The red is blood, yes, but also fire, and light, and soul.

When Kramer compared Bloom’s work to “gefilte fish at a fashionable cocktail party,” he was right that Bloom’s work didn’t fit in with the fashion of his day. Bloom painted representational work just as influential critics like Clement Greenberg proclaimed that the future of painting lay with abstraction.

But Bloom was worse than unfashionable. He didn’t just paint in the wrong style; he didn’t even have a style. His work ranges from the anatomical accuracy of Michelangelo, through the exquisite chiaroscuro of the Baroque, to Pollock’s splattered abstraction. He didn’t have a brand. How, then, was he to make a splash at any of the art world’s fashionable parties?

Instead of a brand, Bloom’s works are tied by a series of spiritual, conceptual threads. His work is animated by paradoxes, pairs of opposing properties. Surface and depth. Emptiness and fullness. Unity and dissection. Life and death. Standing in front of any one of his paintings, I feel these words rub against each other, flint to the flame of spiritual truth.

Such paradoxes were central in Baroque art, and if I had to lump Bloom in with any art-historical movement, it would be the Baroque rather than any twentieth-century current. But Bloom was a Baroque artist only in the sense in which Rembrandt was one. Both artists were fundamentally interested in the human condition. Both reveled in paint — not as mere paint, but as skin, and light, and life. Both had something so much more important than style: soul.

The paradoxes which for a Rubens might only be a technical exercise were, for Bloom, achingly alive. A matter of life and death.

The popularity of the Abstract Expressionists depended on the myth of a linear progression in art. According to this way of thinking, each era comes with one and only one revolutionary style; everything else is reactionary. In her incisive book Hyman Bloom: the Sources of his Imagery, Dorothy Abbott Thompson sketches the history of this myth.

In the 1950s, a new class of wealthy Americans was making its fortunes. Old ways of displaying wealth were falling out of fashion, and

art collecting (…) provided an alternative amusement for the wealthy. (…) An important collection was a testament to the taste, discernment and adventurous nature of the collector (…) Collectors aspired to be both daring and correct — in the lead, and yet sanctioned by the art world.

This aspiration enabled the rise of influential critics such as Clement Greenberg.

Greenberg’s position was that “avant garde,” “modernist,” or “high art” (terms used interchangeably) was difficult and could only be appreciated by those who understood and adhered to the precepts of formalist theory.

The very destructiveness and nihilism of Abstract Expressionism which appalled Bloom ensured the style’s popularity. The paintings were shocking on the outside: collectors could use them to display their discernment and adventurousness. And they were empty on the inside: ready to be filled with fashionable theory that would vindicate the collector’s judgment.

The wide acceptance of Greenberg’s art criticism

among wealthy collectors (many of whom were also museum trustees), museum directors, critics and art historians helped create an interlocking and mutually dependent group that, without being intentionally conspiratorial, determined what sort of art would be treated seriously.

Bloom was one of the unlucky.

Bloom was a mystical and reclusive painter who for a brief time was regarded as a precursor to the Abstract Expressionists. But if the judgment that his work was a precursor to the Abstract Expressionists is a mistake, then — well, so much the worse for the Abstract Expressionists.

Bloom’s mysticism and reclusiveness perfectly explain why he was forgotten. In fact, being reclusive is enough. The real question isn’t why Bloom was forgotten, but why anyone is remembered. Bloom never lived in New York, and eventually moved from Boston to the more provincial Nashua, New Hampshire. How could you be remembered if you stop showing your work?

But even if Bloom had continued to exhibit, his “mysticism” would have ensured failure in the art world. His paintings were religious icons; each brushstroke was a prayer, with no gaps that might be filled with fashion.

What shocked collectors about Bloom’s cadavers weren’t the holes in their center. It was the hope that filled these holes.

When Kramer called Bloom’s paintings “gefilte fish at a fashionable cocktail party,” he wasn’t wrong about the dish Bloom was serving. What he was fundamentally, depressingly confused about was the sort of event Bloom was hosting.

It was never a fashionable party; it was an ecumenical Sabbath.

[1] All quotes from Hyman Bloom: the Sources of his Imagery by Dorothy Abbott Thompson.

[2] One book claims that in the 40s it was illegal to exhibit frontal male nudity, but I haven’t been able to back up the claim elsewhere.

Want more essays about underappreciated painters? Try the one I wrote about Rik Wouters. And if you’d like to receive future essays in your inbox, join my mailing list below.

I knew nothing about Bloom before reading this, and I thoroughly enjoyed the paintings you included in this review alongside your insights. The paintings are mesmerizing, I don’t know about them being difficult to look at in the first place (strangely for me it seems that it’s not the cadaver element, but rather the lack of it, that bothers me, so you might have guessed that my least favorite one among these is the living old woman looking sideways), but it’s definitely impossible to look away once one sets eyes upon them.

LikeLike

I definitely relate to being bothered most by the lack of the cadaver element! The “hard to look” part comes and goes for me. I think the first time I saw them (in reproductions) I also just found them mesmerizing – so glad you get to have that experience too! (The NYT calls his paintings “hard to love,” which made me angry… I basically fell in love with them at first sight.)

LikeLike